segunda-feira, 31 de janeiro de 2005

Sexo

«Eu, que toda a vida me dei com «jovens católicos praticantes» (portugueses), não conheço cinco que sigam «a doutrina da Igreja em matéria sexual». Não é cinco por cento: é mesmo cinco.»

Pedro Mexia

Eu, tal como o Pedro Mexia, sempre me dei com «jovens católicos praticantes», e posso afirmar que conheço cinco que seguem «a doutrina da Igreja em matéria sexual». E admito que sejam mais, talvez chegando mesmo à casa das dezenas. Mas neste caso interessam-me os outros, a maioria. E uma simples observação leva a concluir que não é possível seguir a doutrina da Igreja. No limite, não é. Mas fiquemos por uma interpretação mais pragmática da doutrina: a não existência de sexo fora do casamento. Porque há tão poucos a respeitar esta opção? E, talvez mais pertinente, porque há tão poucos a dar importância a essa opção? Aqueles que se estão marimbando para o apelo à abstinência não parecem estar muito preocupados com esse pecado. Nem por um segundo deixam que isso interfira com a sua Fé (com maiúscula). Sei que não devo tentar extrapolar aquilo que penso: não ligo patavina às questões morais do cristianismo (penitência, arrependimento, sacrifício, etc). Sempre me pareceu que esta busca da santidade ou da pureza de espírito baseada na pureza da carne não tem nenhuma consequência na vida em sociedade. Aliás, é preocupante haver tanta gente que o apregoa mas não o cumpre. Mas voltando a centrar a discussão o que é evidente é que o problema não se põe. Ao nível da moral individual a questão da sexualidade não faz a menor mossa nos jovens. Mas curioso é verificar a sua reacção perante a evidência: o silêncio. Estou convicto que a Igreja, a sua estrutura oficial, não faz a menor ideia do verdadeiro estado das coisas. Porque é raro haver essa discussão. Parece haver ainda um tabu. Se apenas se estivesse a considerar o comportamento íntimo de cada um não perdia dois segundos a pensar nisto. Mas o problema atinge maiores proporções quando interfere com o impacto deste tipo de pensamento no mundo. Não é possível que, baseado na conduta de 2 ou 3% dos católicos (estou a ser generoso), a Igreja continue a condenar o uso do preservativo, por exemplo. Repare-se: esta posição não teria falhas se toda a gente seguisse a doutrina da Igreja em matéria sexual. Mais grave é ainda quando, perante a realidade, o puritanismo oficial radicaliza posições e assume uma atitude de aldeia do Asterix. Daí até à condenação geral dos pecadores vai um passo. A decadência instala-se, artificialmente. Porque há jovens que fornicam sem contrato a civilização está condenada. Não são assim tão poucos os que pensam desta maneira. E depois, claro, há sempre os short-sighted do costume que aproveitam para juntar tudo no mesmo saco: sexo pré-marital, adultério, aborto, homossexualidade, pedofilia (João César das Neves, por exemplo). São eles que se colocam na caverna, imaginando nas sombras projectadas os pecados que incluem nos seus sermões. Bastava-lhes sair da toca, bastava-lhes sair da toca...

Pedro Mexia

Eu, tal como o Pedro Mexia, sempre me dei com «jovens católicos praticantes», e posso afirmar que conheço cinco que seguem «a doutrina da Igreja em matéria sexual». E admito que sejam mais, talvez chegando mesmo à casa das dezenas. Mas neste caso interessam-me os outros, a maioria. E uma simples observação leva a concluir que não é possível seguir a doutrina da Igreja. No limite, não é. Mas fiquemos por uma interpretação mais pragmática da doutrina: a não existência de sexo fora do casamento. Porque há tão poucos a respeitar esta opção? E, talvez mais pertinente, porque há tão poucos a dar importância a essa opção? Aqueles que se estão marimbando para o apelo à abstinência não parecem estar muito preocupados com esse pecado. Nem por um segundo deixam que isso interfira com a sua Fé (com maiúscula). Sei que não devo tentar extrapolar aquilo que penso: não ligo patavina às questões morais do cristianismo (penitência, arrependimento, sacrifício, etc). Sempre me pareceu que esta busca da santidade ou da pureza de espírito baseada na pureza da carne não tem nenhuma consequência na vida em sociedade. Aliás, é preocupante haver tanta gente que o apregoa mas não o cumpre. Mas voltando a centrar a discussão o que é evidente é que o problema não se põe. Ao nível da moral individual a questão da sexualidade não faz a menor mossa nos jovens. Mas curioso é verificar a sua reacção perante a evidência: o silêncio. Estou convicto que a Igreja, a sua estrutura oficial, não faz a menor ideia do verdadeiro estado das coisas. Porque é raro haver essa discussão. Parece haver ainda um tabu. Se apenas se estivesse a considerar o comportamento íntimo de cada um não perdia dois segundos a pensar nisto. Mas o problema atinge maiores proporções quando interfere com o impacto deste tipo de pensamento no mundo. Não é possível que, baseado na conduta de 2 ou 3% dos católicos (estou a ser generoso), a Igreja continue a condenar o uso do preservativo, por exemplo. Repare-se: esta posição não teria falhas se toda a gente seguisse a doutrina da Igreja em matéria sexual. Mais grave é ainda quando, perante a realidade, o puritanismo oficial radicaliza posições e assume uma atitude de aldeia do Asterix. Daí até à condenação geral dos pecadores vai um passo. A decadência instala-se, artificialmente. Porque há jovens que fornicam sem contrato a civilização está condenada. Não são assim tão poucos os que pensam desta maneira. E depois, claro, há sempre os short-sighted do costume que aproveitam para juntar tudo no mesmo saco: sexo pré-marital, adultério, aborto, homossexualidade, pedofilia (João César das Neves, por exemplo). São eles que se colocam na caverna, imaginando nas sombras projectadas os pecados que incluem nos seus sermões. Bastava-lhes sair da toca, bastava-lhes sair da toca...

domingo, 30 de janeiro de 2005

sábado, 29 de janeiro de 2005

Philip Johnson, o imortal

Extraordinária entrevista com Philip Johnson. A ideia era destacar uns excertos. Saiu isto. Aproveitem.

So I suddenly realized -- in the middle of my political work -- I had missed my calling. So, at the age of 34, I decided to really be serious about architecture. Harvard didn't care whether I could draw or not, so I went to Harvard at 34 to study architecture.

I don't see how anybody can go into the nave of Chartres Cathedral and not burst into tears, because I thought that's what everybody would do.

I was a lousy kid. It was when architecture hit me that I became more sensible.

Architecture sometimes seems like politics or religion. It's full of movements and orthodoxies and heresies and controversy. You always seem to be right in the middle of it all.

I love that, you see. I didn't lose that just because I switched from philosophy to architecture. I'm still a thought kind of an architect more than a genius type. I'm not a genius. There are some, and I love them, but I like the give and take and the change and the prophesying what's happening and catching onto the next train by the caboose.

The military is the most important single profession in this country, except for architecture. If it weren't for the military, I couldn't do architecture. So I admire the military very much. That isn't too popular among Harvard intellectuals.

I was a stupid intellectual, you know. The type that wore glasses and went around reading.

Exams are so stupid. I couldn't be bothered to work for them, so I kept flunking them. They were too simple-minded. So I went to a cram school. The cram school said, of course, "You idiot, look at that piece of paper. You've only got six lines on it." I said, "Yeah, the paper's so beautiful, what do you want to spoil it for by covering it with lines," they said, "Look, you've got to pass the exam. Stop your damn theories and cover the sheet with extra trees. It doesn't make any difference, just fill it up. Put more bricks in or something." And another clue, "How do you know how to get into that building?" And I said, "It's right here." They said, "No, you take a red arrow. And it's the only red thing you've got on the sheet, so the examiner will see it" I said, "I see, so he'll know where to go in." Those simple little tricks I had trouble at.

They wanted a house in the suburbs. So I did it, just out of my memory.

To be an architect, you've got to know people. Like most professions. You have to know people in order to get the next job. As the richest and the greatest American architect said, "The first principle of architecture is, get the job." In other words, if you aren't personable enough or persuasive enough, you'll never get anywhere.

I had learned professors that I worshipped -- Russell Hitchcock, a great, great historian of architecture. I wanted to be an architectural historian, that was one of my passing fancies, but I wasn't any good, and this guy was great. And then he tried to build a building. Disaster! In other words, it takes something else besides intellectual prowess. Harvard will never help you become an architect.

It takes what they laughingly call genius, but there are only a couple of geniuses once in a while like an Einstein or a Frank Lloyd Wright. No one can aspire to that. That is either God-given or not. There is nothing you can do about it.

But all of my advice is straight to all kids, "Should I be an architect?" I say "No." Always say no, because if you can help it, don't. Go into something that'll make money, if that's what most Americans seem to want, me included. Just don't bother being an architect.

Le Corbusier I met. He was a nasty man, but obviously a genius. You don't have to like the people just because they're geniuses.

It's the most photographed house [The Glass House]. Bothers the hell out of me. I'm supposed to live there and then people come and look at you all the time. It's annoying.

I can't work if I'm alone.

Now that's another pleasure, to see it come up and watch other people's faces and have them appreciate it. But everybody wants that. That's called the desire for fame. Every movie star has that feeling of wanting to be accepted and be praised. That's a natural ambition in the world. A sense of conquest too. Very, very satisfying, but the trouble is, you mentioned a few very nice buildings, but what about the ninety percent of the other buildings? There's two sides to every one of these coins and I certainly won't talk about those. I only talk about the ones that did come out well.

Is there a difference between designing a house and designing a skyscraper?

It's more difficult. Because every decision you make makes such an enormous percentage difference in the looks. If you get a good plan on a skyscraper, you've got to get somebody's computer -- not mine -- and click it through and it reproduces all the plans all the way up to the hundredth floor. So you have a few basic decisions and then the battles begin.

The only goal is building a beautiful building, but if you don't know your functions, if the Seagram's building didn't work and make piles of money for everybody, it wouldn't be a success. All skyscrapers are money-making machines. So a function of the building, what would rent the best, is always on your mind. You can say, "Oh it's just commercialism," but that commercialism is our non-religion.

The care and feeding of clients is really one of the main obstacles, because you always have a client with some preconceived idea of what a house looks like, and all you want him to do is leave a check and go to Europe for a couple of years. Or leave two checks. But alas, life isn't simple. If it were, more people would be better architects.

I'm not the greatest influence at all, but I am nasty.

My worst mistake was going to Germany and liking Hitler too much.

I mean, how could you? It's just so unbelievably stupid and asinine and plain wrong, morally and every other way. I just don't know how I could have been carried away.

Where the hell was I?! A Harvard graduate! So much for Harvard! I was just stupid. Just unforgivable. That's the worst thing I ever did.

Do you have any thoughts about the role of the architect in society?

I think it's marginal. I don't think it should be marginal. I think it's very important. I think it can influence the world. It can make you a better person if you're surrounded by good architecture, but the world doesn't seem to listen too much to that. They still create cities like Tokyo or Istanbul. Horrible places.

What is architecture's role?

Inspiration, like music. History, like music and painting, used to be called ennobling, but we don't care much about ennoblement anymore. What is it? It makes you feel much better. To be in the presence of a great work of architecture is such a satisfaction that you can go hungry for days. To create a feeling such as mine in Chartres Cathedral when I was 13 is the aim of architecture.

How much is inspiration, how much perspiration?

About 99 percent is perspiration. Anybody can answer that.

Detective novels to keep me from committing suicide. They're wonderful relaxation; much better than television. But I only like the American kind and I read all of them five or six times.

I knew about Mondrian because Mondrian, of course, had a very close connection with architecture. Some painters are more architectonic. The two great ones in recent history are Malevich and Mondrian. If you don't know those people and appreciate them, I don't know how you could be an architect.

My favorite painter for instance, is Caspar David Friedrich. He was a romantic painter. Single men on a dark sea may sound crappy, but I assure you it isn't. A ruined cathedral at sunset may be too appalling to think of, but he could do those pictures. Now you'd say, what's the message? I don't know what message, all I know is every time I go to a museum where there are Caspar David Friedrichs, I spend all my time there.

No writer has ever been able to explain painting. In fact I gave up reading books on painting. (...) So it's best not to talk about it at all. It's magical. That's why they used to say there are many paths to the truth besides reasoning and words and talking. There's mysticism. How do you explain mysticism? How do you find God on your knees in front of a statue. I don't know whether it was God I found at Chartres Cathedral or not. Nobody ever told me that. Those things are mysteries.

But painting is something I can't understand. I cannot paint. I cannot think in those terms at all. I've tried and tried, naturally, always tried. Just as many times I've tried to design a chair. This chair was designed by Mies van der Rohe. Well I can't design a chair. I did it a couple of times and they were not only uncomfortable, but very ugly.

Anybody who makes a prognostication's a damned fool. I've done it and I know it's always, always, always wrong, because you make an assumption that is based on your experience today. The greatest challenge in the next century in architecture? Just the continual anguish and reform and replanning and nobody, nobody knows what strange changes are going to take. The history of the past century, for instance. Nobody could have guessed what Le Corbusier would do, that what Frank Lloyd Wright did was to change the course of history, or Mies van der Rohe.

And now the kids! We have a wonderful generation coming, twisting it all out of what an older person would think was shape. But they're doing it with such panache, with such verve, which such delightful humor, that a whole new panoply of architecture's opened up. That's why, as far as my feeling goes, it's all going to be good.

That is one of the great things about being connected to an art as great as architecture. It's your desire -- Plato's words -- for immortality. That's what keeps you going, not sex.]

[What made you want to be an architect?

I don't know. Because I couldn't do anything else probably. I wasn't very good at anything. My mother was interested in architecture. She wanted a house by Frank Lloyd Wright when she was young, but my father didn't see it the same way, naturally, for obvious reasons, so we compromised by not having one.

I majored in philosophy at Harvard, and I didn't know if I wanted to be a teacher or a theoretician or just what, but I was always interested in art and architecture to look at. I couldn't draw, so I knew I couldn't be an architect, you see.So I suddenly realized -- in the middle of my political work -- I had missed my calling. So, at the age of 34, I decided to really be serious about architecture. Harvard didn't care whether I could draw or not, so I went to Harvard at 34 to study architecture.

I don't see how anybody can go into the nave of Chartres Cathedral and not burst into tears, because I thought that's what everybody would do.

I was a lousy kid. It was when architecture hit me that I became more sensible.

Architecture sometimes seems like politics or religion. It's full of movements and orthodoxies and heresies and controversy. You always seem to be right in the middle of it all.

I love that, you see. I didn't lose that just because I switched from philosophy to architecture. I'm still a thought kind of an architect more than a genius type. I'm not a genius. There are some, and I love them, but I like the give and take and the change and the prophesying what's happening and catching onto the next train by the caboose.

The military is the most important single profession in this country, except for architecture. If it weren't for the military, I couldn't do architecture. So I admire the military very much. That isn't too popular among Harvard intellectuals.

I was a stupid intellectual, you know. The type that wore glasses and went around reading.

Exams are so stupid. I couldn't be bothered to work for them, so I kept flunking them. They were too simple-minded. So I went to a cram school. The cram school said, of course, "You idiot, look at that piece of paper. You've only got six lines on it." I said, "Yeah, the paper's so beautiful, what do you want to spoil it for by covering it with lines," they said, "Look, you've got to pass the exam. Stop your damn theories and cover the sheet with extra trees. It doesn't make any difference, just fill it up. Put more bricks in or something." And another clue, "How do you know how to get into that building?" And I said, "It's right here." They said, "No, you take a red arrow. And it's the only red thing you've got on the sheet, so the examiner will see it" I said, "I see, so he'll know where to go in." Those simple little tricks I had trouble at.

They wanted a house in the suburbs. So I did it, just out of my memory.

To be an architect, you've got to know people. Like most professions. You have to know people in order to get the next job. As the richest and the greatest American architect said, "The first principle of architecture is, get the job." In other words, if you aren't personable enough or persuasive enough, you'll never get anywhere.

I had learned professors that I worshipped -- Russell Hitchcock, a great, great historian of architecture. I wanted to be an architectural historian, that was one of my passing fancies, but I wasn't any good, and this guy was great. And then he tried to build a building. Disaster! In other words, it takes something else besides intellectual prowess. Harvard will never help you become an architect.

It takes what they laughingly call genius, but there are only a couple of geniuses once in a while like an Einstein or a Frank Lloyd Wright. No one can aspire to that. That is either God-given or not. There is nothing you can do about it.

But all of my advice is straight to all kids, "Should I be an architect?" I say "No." Always say no, because if you can help it, don't. Go into something that'll make money, if that's what most Americans seem to want, me included. Just don't bother being an architect.

Le Corbusier I met. He was a nasty man, but obviously a genius. You don't have to like the people just because they're geniuses.

It's the most photographed house [The Glass House]. Bothers the hell out of me. I'm supposed to live there and then people come and look at you all the time. It's annoying.

I can't work if I'm alone.

Now that's another pleasure, to see it come up and watch other people's faces and have them appreciate it. But everybody wants that. That's called the desire for fame. Every movie star has that feeling of wanting to be accepted and be praised. That's a natural ambition in the world. A sense of conquest too. Very, very satisfying, but the trouble is, you mentioned a few very nice buildings, but what about the ninety percent of the other buildings? There's two sides to every one of these coins and I certainly won't talk about those. I only talk about the ones that did come out well.

Is there a difference between designing a house and designing a skyscraper?

It's more difficult. Because every decision you make makes such an enormous percentage difference in the looks. If you get a good plan on a skyscraper, you've got to get somebody's computer -- not mine -- and click it through and it reproduces all the plans all the way up to the hundredth floor. So you have a few basic decisions and then the battles begin.

The only goal is building a beautiful building, but if you don't know your functions, if the Seagram's building didn't work and make piles of money for everybody, it wouldn't be a success. All skyscrapers are money-making machines. So a function of the building, what would rent the best, is always on your mind. You can say, "Oh it's just commercialism," but that commercialism is our non-religion.

The care and feeding of clients is really one of the main obstacles, because you always have a client with some preconceived idea of what a house looks like, and all you want him to do is leave a check and go to Europe for a couple of years. Or leave two checks. But alas, life isn't simple. If it were, more people would be better architects.

I'm not the greatest influence at all, but I am nasty.

My worst mistake was going to Germany and liking Hitler too much.

I mean, how could you? It's just so unbelievably stupid and asinine and plain wrong, morally and every other way. I just don't know how I could have been carried away.

Where the hell was I?! A Harvard graduate! So much for Harvard! I was just stupid. Just unforgivable. That's the worst thing I ever did.

Do you have any thoughts about the role of the architect in society?

I think it's marginal. I don't think it should be marginal. I think it's very important. I think it can influence the world. It can make you a better person if you're surrounded by good architecture, but the world doesn't seem to listen too much to that. They still create cities like Tokyo or Istanbul. Horrible places.

What is architecture's role?

Inspiration, like music. History, like music and painting, used to be called ennobling, but we don't care much about ennoblement anymore. What is it? It makes you feel much better. To be in the presence of a great work of architecture is such a satisfaction that you can go hungry for days. To create a feeling such as mine in Chartres Cathedral when I was 13 is the aim of architecture.

How much is inspiration, how much perspiration?

About 99 percent is perspiration. Anybody can answer that.

Any doubts about your ability?

Oh goodness yes. I'm thoroughly discouraged right now. But that goes with the territory. You see better people around you all the time. Not to be envious and not to take that out in bitterness is a hard lesson, but you'd better, because you can't always be Frank Lloyd Wright. You've got to learn to live in this world just as you live in it. You've got to stand it.

Later on, I became interested in architectural history and my passion in politics. Isaiah Berlin was, to me, the greatest theorist. It's books that really keep the mind filled. Another thing we should advise young people is to read. Read, read, read. If nothing catches your spirit, that's too bad. I must admit that the passion roused by a Plato can have no second. Not even poetry.Detective novels to keep me from committing suicide. They're wonderful relaxation; much better than television. But I only like the American kind and I read all of them five or six times.

I knew about Mondrian because Mondrian, of course, had a very close connection with architecture. Some painters are more architectonic. The two great ones in recent history are Malevich and Mondrian. If you don't know those people and appreciate them, I don't know how you could be an architect.

My favorite painter for instance, is Caspar David Friedrich. He was a romantic painter. Single men on a dark sea may sound crappy, but I assure you it isn't. A ruined cathedral at sunset may be too appalling to think of, but he could do those pictures. Now you'd say, what's the message? I don't know what message, all I know is every time I go to a museum where there are Caspar David Friedrichs, I spend all my time there.

No writer has ever been able to explain painting. In fact I gave up reading books on painting. (...) So it's best not to talk about it at all. It's magical. That's why they used to say there are many paths to the truth besides reasoning and words and talking. There's mysticism. How do you explain mysticism? How do you find God on your knees in front of a statue. I don't know whether it was God I found at Chartres Cathedral or not. Nobody ever told me that. Those things are mysteries.

But painting is something I can't understand. I cannot paint. I cannot think in those terms at all. I've tried and tried, naturally, always tried. Just as many times I've tried to design a chair. This chair was designed by Mies van der Rohe. Well I can't design a chair. I did it a couple of times and they were not only uncomfortable, but very ugly.

Anybody who makes a prognostication's a damned fool. I've done it and I know it's always, always, always wrong, because you make an assumption that is based on your experience today. The greatest challenge in the next century in architecture? Just the continual anguish and reform and replanning and nobody, nobody knows what strange changes are going to take. The history of the past century, for instance. Nobody could have guessed what Le Corbusier would do, that what Frank Lloyd Wright did was to change the course of history, or Mies van der Rohe.

And now the kids! We have a wonderful generation coming, twisting it all out of what an older person would think was shape. But they're doing it with such panache, with such verve, which such delightful humor, that a whole new panoply of architecture's opened up. That's why, as far as my feeling goes, it's all going to be good.

That is one of the great things about being connected to an art as great as architecture. It's your desire -- Plato's words -- for immortality. That's what keeps you going, not sex.]

sexta-feira, 28 de janeiro de 2005

quinta-feira, 27 de janeiro de 2005

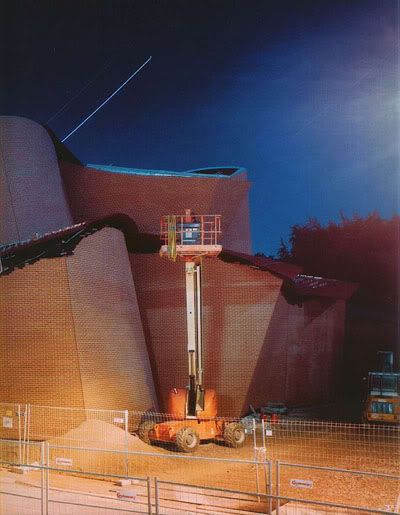

O futuro da arquitectura não é a Casa da Música

Quem o diz é Souto Moura, membro do júri do concurso que atribuiu a vitória à OMA, em entrevista ao Público. Porquê, perguntamos, se a Casa da Música parece estar envolvida nesse manto de futuro? Responde o arquitecto (que diz gostar da obra):

É uma obra de excepção (...) é um pós-modernismo: nós ainda não resolvemos os problemas que ele critica. Koolhaas constrói o não-espaço, faz uma massa e depois tira coisas. Constrói pela negativa. No fundo, é uma desconstrução. (...) É uma certa maneira de ver a arquitectura: desconstruir, tem a ver com Derrida, essas coisas todas. Acho que Portugal durante muitos anos vai precisar de construir - precisamos da gramática da construção e não da desconstrução. A desconstrução é um luxo das sociedades pós-industriais.

Retenho esta ideia chave de que (a) desconstrução é um luxo das sociedades pós-industriais.

Tentei dizer o mesmo anteriormente:

Talvez por isso o desconstrutivismo tenha sido a coisa mais coerente e interessante que o pós-modernismo tenha gerado. Para quem estuda arquitectura e conhece minimamente as suas premissas e códigos, o desconstrutivismo é sempre interessante. (...) Uma obra desconstrutivista é exageradamente elitista. É snob. Só é acessível a alguns. (...) Por isso o desconstrutivismo não resolve nada, não acrescenta nada, não faz a arquitectura andar para a frente. São obras de orçamento elevado.

Serve isto para dizer que a arquitectura é, na sua essência, a arte de resolver problemas. A criatividade é elogiada pela sua capacidade de descobrir soluções. Na mesma entrevista Souto Moura revela: «Não tenho vergonha nenhuma de dizer que andei aflito sempre a fazer o estádio.» A aflição não vem da pressão de se gerar algo de extraordinário. A aflição nasce das dificuldades em resolver questões práticas, geralmente bastante complexas. Que tudo pareça simples e claro como resultado final é prova da mestria do projectista. O desconstrutivismo, por não ter ambições de resolver, não tem interesse em clarificar. Serve para as excepções, como a Casa da Música, mas o futuro da arquitectura não é, de facto, por aí.

É uma obra de excepção (...) é um pós-modernismo: nós ainda não resolvemos os problemas que ele critica. Koolhaas constrói o não-espaço, faz uma massa e depois tira coisas. Constrói pela negativa. No fundo, é uma desconstrução. (...) É uma certa maneira de ver a arquitectura: desconstruir, tem a ver com Derrida, essas coisas todas. Acho que Portugal durante muitos anos vai precisar de construir - precisamos da gramática da construção e não da desconstrução. A desconstrução é um luxo das sociedades pós-industriais.

Retenho esta ideia chave de que (a) desconstrução é um luxo das sociedades pós-industriais.

Tentei dizer o mesmo anteriormente:

Talvez por isso o desconstrutivismo tenha sido a coisa mais coerente e interessante que o pós-modernismo tenha gerado. Para quem estuda arquitectura e conhece minimamente as suas premissas e códigos, o desconstrutivismo é sempre interessante. (...) Uma obra desconstrutivista é exageradamente elitista. É snob. Só é acessível a alguns. (...) Por isso o desconstrutivismo não resolve nada, não acrescenta nada, não faz a arquitectura andar para a frente. São obras de orçamento elevado.

Serve isto para dizer que a arquitectura é, na sua essência, a arte de resolver problemas. A criatividade é elogiada pela sua capacidade de descobrir soluções. Na mesma entrevista Souto Moura revela: «Não tenho vergonha nenhuma de dizer que andei aflito sempre a fazer o estádio.» A aflição não vem da pressão de se gerar algo de extraordinário. A aflição nasce das dificuldades em resolver questões práticas, geralmente bastante complexas. Que tudo pareça simples e claro como resultado final é prova da mestria do projectista. O desconstrutivismo, por não ter ambições de resolver, não tem interesse em clarificar. Serve para as excepções, como a Casa da Música, mas o futuro da arquitectura não é, de facto, por aí.

O professor

Disseram-me uma vez (uma ex-aluna) que o prof. Freitas é bom professor; que fala bem; que tem retórica; que o discurso é bom e fácil; que sabe argumentar; que é apelativo. Mas que falha no conteúdo, bastante desinteressante e pouco aprofundado. Tudo explicado: Freitas do Amaral pede maioria absoluta para o PS nas próximas eleições.

quarta-feira, 26 de janeiro de 2005

O Benfica ganhou ao Sporting

Mas o que realmente interessa é que amanhã, pelas oito e meia da matina, Roger Federer vai jogar. Acho que é o Safin, o outro, mas isso também não interessa.

Xô doutor

Vitória por K.O. técnico ao segundo assalto para Ricardo Araújo Pereira. A tarefa era fácil, diga-se. A argumentação d'O Acidental foi (surpreendentemente) bastante superficial e sem qualquer hipótese de resistir. Apenas uma mancha impede a vitória do Ricardo de ser apelidada de imaculada: a tentativa de separar um suposto comunismo dos livros (Marx) do comunismo real:

«Não vejo que haja qualquer nexo de coerência entre considerar que as críticas de Marx à sociedade capitalista são acertadas e aprovar o que fez Estaline. Do mesmo modo, não é verdade que é possível continuar a ser cristão depois de todos os horrores praticados por cristãos em todo o mundo? Ou é forçoso que quem segue a doutrina de Cristo se reveja em Torquemada?»

Esta comparação não tem qualquer sentido. Teria se o comunismo pudesse ter essas duas faces que o Ricardo gostaria (e gostará) que existissem, e que se pode argumentar que existe no cristianismo, por exemplo. Mas o que a história diz é que o comunismo é monofacial, não há o reverso, só a cara.

P.S: Escrevi este post mentalmente a caminho de casa (sim, tenho problemas). Por isso só agora vi este post do Luciano Amaral. É impossível não dar razão ao Luciano, mas considero que esta já é outra batalha. A inicial, a tal que foi ganha pelo Ricardo por K.O. técnico, era sobre a sua legitimidade ou não de ter opinião política. Quanto à tentativa de defesa do comunismo aí o Ricardo não tem hipótese.

«Não vejo que haja qualquer nexo de coerência entre considerar que as críticas de Marx à sociedade capitalista são acertadas e aprovar o que fez Estaline. Do mesmo modo, não é verdade que é possível continuar a ser cristão depois de todos os horrores praticados por cristãos em todo o mundo? Ou é forçoso que quem segue a doutrina de Cristo se reveja em Torquemada?»

Esta comparação não tem qualquer sentido. Teria se o comunismo pudesse ter essas duas faces que o Ricardo gostaria (e gostará) que existissem, e que se pode argumentar que existe no cristianismo, por exemplo. Mas o que a história diz é que o comunismo é monofacial, não há o reverso, só a cara.

P.S: Escrevi este post mentalmente a caminho de casa (sim, tenho problemas). Por isso só agora vi este post do Luciano Amaral. É impossível não dar razão ao Luciano, mas considero que esta já é outra batalha. A inicial, a tal que foi ganha pelo Ricardo por K.O. técnico, era sobre a sua legitimidade ou não de ter opinião política. Quanto à tentativa de defesa do comunismo aí o Ricardo não tem hipótese.

Mailbox: Criação e Crítica

«É complexo demais falar sobre o assunto conceito-arte, justamente porque estou nos dois opostos (pra mim os dois, arte e conceito, jamais deixarão de ser opostos). Sou artista plástica e ao mesmo tempo futura crítica de arte. E ando percebendo que não sei se conseguirei ser uma crítica, tenho ainda muito mais o lado irracional da criação (que eu nunca quero que deixe de existir) do que o lado crítico da análise. Afinal - como você bem disse no seu texto - como chegar a “um atalho que só eles conhecem e que deixa toda a gente desarmada”? Como sou jovem, nos poucos anos que tive de carreira e nas entrevistas que tive que dar antes das aberturas de exposição, JAMAIS soube explicar com perfeitas palavras sobre meu trabalho, o pior é que eles (os jornalistas) já estão se acostumando com os artistas de bulas nas mãos, e sabe quem são? Aqueles que MORRERIAM ou não existiriam sem uma explicação totalmente complexa e confusa do que criam.»

Cris

Cris

terça-feira, 25 de janeiro de 2005

A piada do mês

«Marxismo-leninismo

Pelo que se viu no debate com Portas, Louçã foi a um daqueles cirurgiões que há agora que fazem a reconstrução do hífen.»

Rui Branco, no Esplanar

Pelo que se viu no debate com Portas, Louçã foi a um daqueles cirurgiões que há agora que fazem a reconstrução do hífen.»

Rui Branco, no Esplanar

Daily Show

Só agora percebi que o Pedro Mexia tem uma coluna diária no DN, Ministério da Cultura. É uma boa notícia, para o DN e para nós.

segunda-feira, 24 de janeiro de 2005

Sontag tem razão

Recentemente, num jantar de amigos, discutia-se Paula Rego. A admiração pela simplicidade do discurso era generalizada: Paula Rego tem respostas desconcertantes e afirmações muito cruas sobre o que faz. Quando confrontada com a forte simbologia de uma rosa num quadro seu, Paula Rego respondia que apenas tinha pintado a rosa porque esse canto do quadro lhe parecia muito vazio. Os exemplos são muitos e todos dentro da mesma lógica. O ponto importante nesta história era evidente: o artista nem sempre sabe o que faz. A intuição (ou outra coisa qualquer) gera um impulso irreflectido que só mais tarde, a posteriori, aparece descodificado por um terceiro: o crítico. Agora, é legítimo colocar a questão: qual a importância dessa análise, quando manifestamente é algo exterior à obra, para a valorização da arte? Eu, que depois do quinto copo já não meço as palavras, disparava com Susan Sontag e o seu Against Interpretation, mas ao mesmo tempo reconhecia inteira autoridade ao crítico. Talvez esteja aqui o material de que são feitos os grandes: chegar lá sem saber, ou chegar lá através de um atalho que só eles conhecem e que deixa toda a gente desarmada. Paula Rego sabe muito bem que a sua obra não se reduz a rosas que enchem cantos de quadros vazios, mas ao recusar voluntariamente falar sobre o seu trabalho noutro nível que não esse, está, e muito bem, a centrar a questão no essencial, o que nos leva outra vez a Sontag.

Na altura fiz o paralelo com Souto Moura (não me lembrando que recentemente foi anunciado a construção do Museu Paula Rego, em Cascais, desenho do próprio, o que se assume como uma coincidência feliz). Souto Moura possui essa qualidade (que deixa sempre a dúvida de ser intencional ou não) de reduzir o seu trabalho a um discurso simples, quase simplista, de palavras secas e desconcertantes. «Faço as coisas porque me parecem bem», dispara, pondo de lado qualquer intenção intelectual de afirmação pessoal. Quer isto dizer que as palavras que são escritas sobre a sua obra o surpreendem? Quer isto dizer que, à semelhança de Paula Rego, Souto Moura não sabe o que faz? A resposta é óbvia e serve para descobrir a intencionalidade da atitude. Os adjectivos são correctos e colam-se bem à arte. Mas se a arte (e isto é que Souto Moura e Paula Rego sabem bem) só se descobre depois dos adjectivos, então os adjectivos serão, provavelmente, errados.

Na altura fiz o paralelo com Souto Moura (não me lembrando que recentemente foi anunciado a construção do Museu Paula Rego, em Cascais, desenho do próprio, o que se assume como uma coincidência feliz). Souto Moura possui essa qualidade (que deixa sempre a dúvida de ser intencional ou não) de reduzir o seu trabalho a um discurso simples, quase simplista, de palavras secas e desconcertantes. «Faço as coisas porque me parecem bem», dispara, pondo de lado qualquer intenção intelectual de afirmação pessoal. Quer isto dizer que as palavras que são escritas sobre a sua obra o surpreendem? Quer isto dizer que, à semelhança de Paula Rego, Souto Moura não sabe o que faz? A resposta é óbvia e serve para descobrir a intencionalidade da atitude. Os adjectivos são correctos e colam-se bem à arte. Mas se a arte (e isto é que Souto Moura e Paula Rego sabem bem) só se descobre depois dos adjectivos, então os adjectivos serão, provavelmente, errados.

Braga

A prova provada de como a arquitectura é determinante e influencia realmente o comportamento humano é que o Sporting de Braga está a 1 ponto dos primeiros, e é a equipa que mais pontos somou em casa até agora.

sábado, 22 de janeiro de 2005

links

A lista links ali em baixo precisa de umas voltas. Para já inclui-se Os (In)separáveis, um blogue que leio já há algum tempo.

sexta-feira, 21 de janeiro de 2005

quinta-feira, 20 de janeiro de 2005

Medo de ser feliz

Da imensa gramática do futebolês esta é das expressões que mais vezes parece fazer sentido. Fora do futebol, claro está.

Pela calada da noite

Segundo o Frescos (insuspeito) este blogue foi actualizado às 4:26 da madrugada de hoje. Acontece que sou o único que pode fazê-lo e a essa hora, julgava eu, estava a dormir profundamente. Exactamente: há mais um sonâmbulo para as estatísticas.

Direitos de autor

Este é um caso muito interessante que dá pano para mangas:

«Estoril-Sol Vai Contestar Pedido de Embargo do Novo Casino de Lisboa

(...)Os arquitectos do pavilhão - Paula Santos, Miguel Guedes e Rui Ramos - apresentaram, a 7 de Janeiro, uma acção no Tribunal Cível de Lisboa, invocando ter a obra do novo casino começado sem a sua autorização quanto às alterações em curso(...)»

quarta-feira, 19 de janeiro de 2005

O que é a arquitectura? A abordagem antropológica

«O objecto original da arquitectura é, portanto, o da construção do espaço socializado, apropriado pelo homem. É a produção concreta, efectiva, prática do espaço da cultura e da norma no interior da natureza, espaço em redor do qual a natureza se encontra, então, disposta e ordenada pelo homem como mundo, e no qual a própria sociedade se encarna de modo sensível.»

Michel Freitag, Arquitectura e Sociedade

Michel Freitag, Arquitectura e Sociedade

Desejo que infelizmente me parece impossível

Ver Dirty Harry rebentar, à queima-roupa e à porta de casa, Michael Moore.

terça-feira, 18 de janeiro de 2005

A bola

«O modo como o angolano, depois de uma eternidade sem jogar, corre com a bola que o Simão lhe passou, sentindo a pressão do defesa, pobre coitado de camisola aos quadradinhos, mas mostrando uma soberana indiferença, apenas interessado na baliza; o modo como levanta os olhos fixando o alvo; e o modo como, por fim, numa espécie de contra-tempo que apanha todos desprevenidos, jogadores, treinadores, adeptos no estádio, telespectadores, ouvintes da rádio, e remata cruzado, rente à relva, quase com gentileza, golo, golo, goooolo!, é acontecimento de sim e sim sem igual. (Para citar os poetas, não há palavras.)»

Jacinto Lucas Pires, in A Capital

Jacinto Lucas Pires, in A Capital

«Architects Behaving Badly»

Ignoring Environmental Behavior Research, by Thomas Fisher

«Since architecture centrally involves constructing environments for people, why has the architectural community largely ignored environmental psychology, the field that analyses how well we do in meeting people’s needs? Is it that we don’t want to know or, even more troubling, that we don’t care how we’re doing? Or have our various modern and postmodern ideologies gotten in the way, allowing us to convince ourselves that the enormous literature in environmental behavior has little relevance to either the discipline or practice of architecture? And is it time, as architecture has become much less ideological and much more tolerant of difference, to look again at what environmental psychology has to offer us?

[...]

Understanding “the other,” though, rarely happens without resistance. Architects, for example, sometimes complain that environmental behavior research uncovers the obvious, and when you scan the abstracts in the major journals in the field—Environment and Behavior, Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, Journal of Environmental Psychology—you will find a lot that does seem self-evident: inner city children benefit from green space, windows in the workplace improve job satisfaction, aesthetically pleasing stairwells increase their use, and ventilation affects worker performance.

And yet how much does this claim of obviousness stem from our own desire to avoid facing up to what we, as architects, have done over the last fifty years? What this research really makes obvious is that we have been designing cities without green space, workplaces without windows, offices without adequate ventilation, and stairwells from hell, and this points toward a much broader critique of the architectural community.(...) No wonder many architects don’t want to read this literature.

[...]

Nevertheless, many architecture faculty, especially design faculty, dislike environmental behavior research because it seems too deterministic or too simplistic when researchers use the results of their work to drive form-making too directly, without all of the other factors affecting design taken into account. While studio faculty don’t hesitate giving students all kinds of other determinants of form, the neglect of social science research in architecture studios stems from a deeper divide. Environmental psychology has a strong empirical, functional, and instrumental bias, measuring people’s behavior in order to change environments to improve our chances of being healthier, happier, and/or more productive. Architectural theory over the last forty years has gone in almost the opposite direction, with an ideological, formal, and skeptical tilt. This has led to a studio culture that focuses on propositions more than measurements, aesthetics more than human activity, and speculation more than demonstration.

[...]

Not everyone can know everything, and the enormity of the environmental psychology literatuire can be a deterrent to architects' command of it. Still, that is no excuse for the outright neglect of this research by architects over the last serveral decades. If nothing else, environmental behavior studies can help us see how much the architecture culture is, itself, an environment in which we beahve in often unexplained ways, based on unspoken assumptions, and resulting in unanticipated consequences. Were we to become more self-conscious and self-critical of our own professional and disciplinary culture, we would find that envioronmental psychology has much to offer, not least of which, like all good psychology, is an understanding of ourselves.»

«Since architecture centrally involves constructing environments for people, why has the architectural community largely ignored environmental psychology, the field that analyses how well we do in meeting people’s needs? Is it that we don’t want to know or, even more troubling, that we don’t care how we’re doing? Or have our various modern and postmodern ideologies gotten in the way, allowing us to convince ourselves that the enormous literature in environmental behavior has little relevance to either the discipline or practice of architecture? And is it time, as architecture has become much less ideological and much more tolerant of difference, to look again at what environmental psychology has to offer us?

[...]

Understanding “the other,” though, rarely happens without resistance. Architects, for example, sometimes complain that environmental behavior research uncovers the obvious, and when you scan the abstracts in the major journals in the field—Environment and Behavior, Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, Journal of Environmental Psychology—you will find a lot that does seem self-evident: inner city children benefit from green space, windows in the workplace improve job satisfaction, aesthetically pleasing stairwells increase their use, and ventilation affects worker performance.

And yet how much does this claim of obviousness stem from our own desire to avoid facing up to what we, as architects, have done over the last fifty years? What this research really makes obvious is that we have been designing cities without green space, workplaces without windows, offices without adequate ventilation, and stairwells from hell, and this points toward a much broader critique of the architectural community.(...) No wonder many architects don’t want to read this literature.

[...]

Nevertheless, many architecture faculty, especially design faculty, dislike environmental behavior research because it seems too deterministic or too simplistic when researchers use the results of their work to drive form-making too directly, without all of the other factors affecting design taken into account. While studio faculty don’t hesitate giving students all kinds of other determinants of form, the neglect of social science research in architecture studios stems from a deeper divide. Environmental psychology has a strong empirical, functional, and instrumental bias, measuring people’s behavior in order to change environments to improve our chances of being healthier, happier, and/or more productive. Architectural theory over the last forty years has gone in almost the opposite direction, with an ideological, formal, and skeptical tilt. This has led to a studio culture that focuses on propositions more than measurements, aesthetics more than human activity, and speculation more than demonstration.

[...]

Not everyone can know everything, and the enormity of the environmental psychology literatuire can be a deterrent to architects' command of it. Still, that is no excuse for the outright neglect of this research by architects over the last serveral decades. If nothing else, environmental behavior studies can help us see how much the architecture culture is, itself, an environment in which we beahve in often unexplained ways, based on unspoken assumptions, and resulting in unanticipated consequences. Were we to become more self-conscious and self-critical of our own professional and disciplinary culture, we would find that envioronmental psychology has much to offer, not least of which, like all good psychology, is an understanding of ourselves.»

O ombro

Brad Pitt separou-se da mulher. A decisão foi tomada durante a rodagem de Mr. and Mrs. Smith, onde contracena com Angelina Jolie. Tudo explicado, dirão os mais atentos. Mas Angelina vem agora dizer que apenas ofereceu o «ombro para chorar as suas mágoas.» Eu não sei em que mundo vive a menina Jolie, mas no meu o (seu) ombro é mais do que suficiente.

segunda-feira, 17 de janeiro de 2005

Odd

Paulo Cunha e Silva escreveu ontem uma perturbada crónica sobre a Casa da Música:

«A Casa da Música é um dos mais perturbantes objectos da paisagem cultural portuguesa. É perturbante metonimicamente. Quer dizer, é perturbante nas formas mas também nos conteúdos. É perturbante no processo, no método, mas também nos resultados. É um objecto perturbante e absolutamente perturbado. Como se a sua natureza compulsasse a natureza do mundo. Ela é perturbada e é também um foco de perturbação. É por isso, uma forma, um objecto, com conteúdo fascinante.»Continua, a falar do edifício. Mas o mais perturbante disto tudo é que Cunha e Silva não consegue escever uma linha que seja sobre o edifício, um argumento, uma análise, por mais simplista que seja. Limita-se a dizer que é um objecto «perturbante», que cria «rupturas», e que «cai do céu como um projéctil que a balística não fez chegar ao destino». O que não chega, não chega mesmo. O elogio à arquitectura baseado apenas na diferença não interessa. É estéril e sem consequências. O que perturba no meio disto tudo é a sensação que fica que isto pode ser uma opinião generalizada: a Casa da Música é um sucesso porque é um objecto estranho. Apenas por isso. Talvez a arquitectura seja uma arte, e como arte possa estar abrangida pela premissa de Sontag, against interpretation. No aspecto meramente formal da coisa, diga-se. Mas, e se a democracia é para ser levada ao extremo (não consigo pensar em Koolhaas sem ser um animal político), isso significaria que o direito à diferença é para todos. Repare-se, é o direito, não o dever. Assim este culto pela diferença aliado ao direito de ser diferente poderá gerar situações bastante desagradáveis. O melhor é que é se esfriem os dois, o culto e o direito.

Mailbox: Centros

«Eu também concordo, a rua é a unidade urbana por excelência. Os canais de circulação, as linhas que estruturam a malha urbana e através das quais configuramos a nossa mais comum imagem da cidade, quando as percorremos. Não acredito que alguém prefira o ambiente de redoma dos centros comerciais ao da rua, mas só quando esta está bem tratada e respeitada. Já o centro comercial oferece de tudo um pouco o que a sociedade de consumo rápido necessita. O horário, a impessoalidade, a diversidade concentrada, o conhecimento prévio do que se vai encontrar, a arrumação, a limpeza e a segurança. Mas o que faz os centros ganharem não é simplemente a segurança nem os outros mais. É o estacionamento. Imaginemos este cenário perfeito: o indivíduo sai do seu condomínio, de carro, pela garagem, faz todo o caminho pelos acessos rápidos até entrar no estacionamento do centro. Compras feitas, voltinha dada, eis que regressa pelo mesmo caminho. Facilidade total, há que reconhecer. Experiência urbana, zero. A vitória dos centros comerciais é proporcional ao declínio da qualidade do espaço público. A facilidade do novo mundo de consumo deixa as ruas e praças mais desertas. Sem estacionamento e acessibilidade rápida, não há facilidade. Maior parte, isto é um problema de acessos e estacionamento. Para o diagnóstico completo, a doença que falta referir: a desertificação dos centros urbanos, as zonas consolidadas, sobretudo o histórico, com a perca da população residente para a periferia e suburbio. Os suburbios e periferia cresceram sem infraestruturas planeadas. São pedaços desagregados. Os centros comerciais, os grandes, colocam-se lá, onde podem e onde é preciso. Periferia, e até suburbio mais recentemente. A combinação é perfeita. Como no ditado “Juntou-se a fome à vontade de comer”. O centro comercial é o tudo, onde não havia nada.

O Campera e o Freeport são propostas de consumo ainda mais radicais. Para compensar, simulam pequenas aldeias tradicionais. Ao contrário do Colombo, estes não tem matéria-prima constante à sua volta de onde se alimentar da mesma maneira massiva. É uma questão de moda. E não se vai à feira popular todos os dias.»

Susana

ACT: Só agora percebi que o original está aqui.

O Campera e o Freeport são propostas de consumo ainda mais radicais. Para compensar, simulam pequenas aldeias tradicionais. Ao contrário do Colombo, estes não tem matéria-prima constante à sua volta de onde se alimentar da mesma maneira massiva. É uma questão de moda. E não se vai à feira popular todos os dias.»

Susana

ACT: Só agora percebi que o original está aqui.

domingo, 16 de janeiro de 2005

Plan B

Plan B. Teatro abstracto sobre a descoberta e a experimentação do meio ambiente, também ele abstracto mas muito palpável. O horizontal e o vertical confundem-se num palco que desafia constantemente a gravidade e a relação natural das coisas. Pelo meio muita energia gasta para reconhecer todos os cantos à casa. Quatro homens, anónimos, à descoberta (individual e colectiva) das fronteiras de um mundo do tamanho de um palco, onde afinal de contas cabe muito mais do que se esperaria. Ah, e é muito divertido.

sábado, 15 de janeiro de 2005

Centros descentrados

Manuel Graça Dias atira-se hoje aos Centros Comerciais (Única, pags. 40 e 41). O artigo é bom, como de costume, e tem como linha condutora a comparação dos shoppings com a cidade, a cidade verdadeira, da rua, do comércio tradicional. Aqui reside talvez o problema da coisa: será justa esta comparação? Será esta a comparação que deve ser feita? MGD apelida os shoppings como um «sufoco seguro», um sítio que imita a cidade (o artigo intitula-se A imitação da cidade), mas uma cidade inexistente: «A "cidade-ideal", para os cérebros inventores destas "máquinas de consumo", cuja imaginação não vai mais longe do que o passeio à Disneylândia ou aos parques temáticos dos arredores de Barcelona, é uma cidade já só de peões (primeira contradição), com corredores a fazerem de ruas, à volta dos quais se posicionam as lojas da globalização, por dentro de um enorme contrentor ou barracão mais ou menos festivo, de clima condicionado e permanentemente vigiado.» Neste frente-a-frente, cidade vs. shopping, o resultado é previsível: ganha o shopping porque é mais «seguro» e «confortável». E a segurança e o conforto ainda são, talvez, as duas características que o cidadão comum (de todas as classes) mais deseja nos seus ambientes: seja em casa, no trabalho, ou no centro comercial. A deturpação da vida urbana que daqui decorre não deixa de ser alarmante. O espaço público vai perdendo importância. Hoje o contacto preferido é o contacto directo: o acaso, o não esperado, o adicional não interessa. A multiplicidade de vivências que (só) a cidade permite vai sendo gradualmente substituída por um conjunto de relações pessoa-a-pessoa, numa analogia clara com o mundo virtual. A rua vai-se transformando num canal utilitário, num meio que serve um fim, deixando de ser, ela própria, um fim em si mesmo. O problema é que não se vê solução. Não se percebe como podem o comércio sair do shopping e voltar para a rua, a praça, como (ainda) acontece «na civilizada Alemanha ou na educada França». Mais: estaremos condenados a viver junto aos acessos da autoestrada (juntando aos shoppings os parks empresariais)? Das quatro actividades enunciadas na Carta de Atenas (habitar, trabalhar, circular, e lazer), só a habitação ainda resiste à rodovia. Até quando?

Rua, prédio: Brasília

«Curioso isso que você diz da rua, prédio, edifício...Ando pensando sobre isto sempre que comparo as ruas da cidade que vivo (Brasília), que são únicas, com as do resto do mundo. Todos os conceitos que temos sobre ruas caem por água abaixo quando se conhece as de Brasília. E por mais que às vezes irritem os argumentos corbuseanos, tenho que admitir que toda aquele idéia desenvolvida por Corbusier do “ bem viver” acontece relativamente bem aqui nessa cidade moderna. Só o que me deixa desconfortável é constatar isso: que de verdade tudo corre bem na esfera funcional dessa cidade, ruas despoluídas, áreas pro esporte e lazer, verde, verde e mais verde, pulmões limpos (Corbusier ficaria feliz de ver isso, alias ele viu), mas falta a essência do que seja mesmo uma RUA TRADICIONAL, talvez isso que temos aqui tenha que ter um outro nome, porque faltam aqui: ruelas toscas - mas lindas, becos lúdicos e, o que mais sinto falta, as ladeiras!»

Cris

Cris

sexta-feira, 14 de janeiro de 2005

cidade

Na cidade tradicional é «a minha rua». Na cidade moderna é «o meu prédio». Apesar de serem coisas diferente, ruas e prédios, neste caso desempenham um papel semelhante, o da pertença a um sítio. Pode falar-se em bairro também, mas o bairro não chega para desenhar todos os contornos do território de pertença; por vezes o bairro é demasiado grande, e dentro do bairro há que distinguir ruas ou prédios. Repare-se que são mutuamente exclusivos: quando se fala de rua não se pode falar de prédio e vice-versa.

Na rua todos os prédios de alinham num sentido colectivo para dar forma a uma entidade mais importante. Não se distinguem, não são únicos. Geralmente, quase sempre, na rua os edifícios respeitam o vizinho, ou seja, copiam-lhe a métrica, a proporção, a côr, os materiais. Tudo, lembre-se, porque é a rua que assim o obriga.

Quando se fala no prédio a primeira coisa a notar é que não se fala no edifício. Não é só a palavra que é mais comunicativa (menos sílabas, sílaba tónica aberta, etc.), mas é a subtil diferença de significado: o edifício é a coisa construída, só, é o betão e a pedra, a caixilharia e os tubos de esgoto; o prédio, por sua vez, é o edifício habitado, são as relações de vizinhança entre pisos e apartamentos. O prédio define logo um ambiente, tal como a rua.

Eu prefiro a rua. Nunca tive um prédio, é certo, mas ainda assim a rua continua a ser para mim a unidade urbana por excelência. É por isso que, por exemplo, prefiro Alvalade aos Olivais.

Na rua todos os prédios de alinham num sentido colectivo para dar forma a uma entidade mais importante. Não se distinguem, não são únicos. Geralmente, quase sempre, na rua os edifícios respeitam o vizinho, ou seja, copiam-lhe a métrica, a proporção, a côr, os materiais. Tudo, lembre-se, porque é a rua que assim o obriga.

Quando se fala no prédio a primeira coisa a notar é que não se fala no edifício. Não é só a palavra que é mais comunicativa (menos sílabas, sílaba tónica aberta, etc.), mas é a subtil diferença de significado: o edifício é a coisa construída, só, é o betão e a pedra, a caixilharia e os tubos de esgoto; o prédio, por sua vez, é o edifício habitado, são as relações de vizinhança entre pisos e apartamentos. O prédio define logo um ambiente, tal como a rua.

Eu prefiro a rua. Nunca tive um prédio, é certo, mas ainda assim a rua continua a ser para mim a unidade urbana por excelência. É por isso que, por exemplo, prefiro Alvalade aos Olivais.

quinta-feira, 13 de janeiro de 2005

Isn't it ironic?

A notícia é já antiga, mas já que se fala em Gehry aqui vai:

New L.A. concert hall raises temperatures of neighbors

Ao que parece, a luz reflectida pelas superfícies metálicas do edifício tem provocado na vizinhança um aumento de temperatura considerável. Os automobilistas também se queixam da luz excessiva. A conclusão é fácil: o edifício de Gehry é demasiado brilhante. O que não deixa de ter a sua graça.

New L.A. concert hall raises temperatures of neighbors

Ao que parece, a luz reflectida pelas superfícies metálicas do edifício tem provocado na vizinhança um aumento de temperatura considerável. Os automobilistas também se queixam da luz excessiva. A conclusão é fácil: o edifício de Gehry é demasiado brilhante. O que não deixa de ter a sua graça.

quarta-feira, 12 de janeiro de 2005

E o júri de NY dá as seguintes pontuações:

O maradona explicou, preto no branco:

«Há quem não ligue a essas coisas, mas esses não são verdadeiros bloggers. Quem tenta desviar a atenção da actividade blogueira do ‘quem-linka-quem’ para o ‘quem escreve melhor’, tem ‘mais graça’ ou é ‘mais inteligente’ não me merece mais consideração que os escritores que decidem passar ao papel as suas opiniões sobre futebol.»Serve isto para dizer que A Memória Inventada cometeu o deslize, o erro, a desatenção, ou, vá lá, a extrema gentileza de linkar este blogue. Escusado será dizer: exijo, a partir de hoje, ser alvo de tratamento formal, senhor incluído. E vai desde já o agradecimento ao Tulius Detritus (e um abraço para o Ivan e para o Difool, o Tulius que se encarregue disso quando os vir).

causa-efeito

Da entrevista que José Forjaz concede à Arquitectura e Vida deste mês retive especialmente esta passagem:

Dedicado ao Ma-schamba, a quem aproveito para recomendar a entrevista na íntegra.

«- A projecção dos telhados constitui uma das características da sua obra. A que se deve este facto?

- Durante anos fiz empenas, paredes contra as quais bate um telhado. Neste momento já não faço; as coberturas passam todas para fora das paredes. Estou a falar exactamente do facto de ao fim de 25 anos ter reconhecido que não há nenhum artesão em Moçambique, ou naquela parte de África, que me faça uma vedação, um rufo, bem feito e sem verter água.»

Dedicado ao Ma-schamba, a quem aproveito para recomendar a entrevista na íntegra.

terça-feira, 11 de janeiro de 2005

Colagem

Pelas imagens há, de facto, um problema de escala. O (actual) universo formal de Frank Gehry não dá para tudo. A "culpa" não será dele mas sim de quem exige pequenas réplicas de Bilbau (ou do Walt Disney Concert Hall, projecto anterior a Bilbau mas construído posteriormente). Gehry podia recusar, claro, podia propôr outra coisa. Mas que paga não quer outra coisa, quer a coisa, a mesma coisa. Desta vez tratou-se de uma ampliação, uma adição de novos objectos a uma pré-existência que definiu à partida a escala. Percebe-se que este estranho tenta dialogar ou, pelo menos, não falar ao mesmo tempo. Mas o resultado é estranho porque paradoxalmente estas imagens já não são novas. Estamos habituados é a vê-las noutra escala, noutro contexto. Aqui torna-se evidente a colagem. Evidente e desnecessária. Neste caso o que brilha são os planos verticais de cobertura. Os horizontais são de revestimento cerâmico, baço. Como que a reconhecer que não há espaço, não há ângulo, não há dimensão: para se poder contemplar a obra em todo o seu esplendor é necessário subir à cobertura do edifício vizinho. Isso ou passar de helicópetro.

Sou só eu ou há aqui um problema de escala?

Museum MARTa, Herford, Alemanha - Frank Gehry

fotografia (pormenor) de Roel Backaert, publicada na A10

fotografia (pormenor) de Roel Backaert, publicada na A10

segunda-feira, 10 de janeiro de 2005

bolsa de emprego

via RandomBlog:

Um tipo vai a caminhar pela rua quando, de repente, um assaltante mascarado, lhe aponta uma arma e diz:

- Passa o relógio!

O coitado dá-lhe o "Rolex" falso e o gatuno reclama:

- O que é isto? Esta merda vende-se na Feira da Ladra por 5 euros!... Passa, mas é a carteira, porra!

O pobre do homem alcança a carteira de plástico, imitação de "Pierre Cardin" e o assaltante descobre 3 bilhetes pré-comprados de autocarro, duas senhas refeição e 2 euros.

O ladrão, já furioso, agarra-lhe nos colarinhos e diz-lhe:

- És uma bela bosta, pá...! O teu fato está gasto, os teus sapatos ainda estão piores e a única coisa que parece que presta é uma reles imitação barata! Afinal, que merda fazes na vida?

O tipo responde, quase a chorar:

- Ah... Sou arquitecto!

E o ladrão, tirando a máscara, pergunta com um sorriso simpático:

- A sério??? Qual era a tua turma?

domingo, 9 de janeiro de 2005

Estou com uma dor de cabeça daquelas

E está a Paula Rego na televisão a dizer «não gosto nada da natureza.»

Sebastião Salgado por Alexandre Soares Silva

Está ali:

«Nunca houve uma pessoa com cara de digna no mundo que não parecesse ridícula, sejam pescadores ou dentistas ou o que seja, e o trabalho de Sebastião Salgado basicamente consiste em gritar três coisas para seus fotografados: "Faz cara de digno aí", "Sofre mais bonito" e "Sofre naquela sombra ali".»

sábado, 8 de janeiro de 2005

What if?

«- So which contemporary programme would you really like do dramatize through architecture?

- A car park. The only open spaces in a city are parks and car parks. Maybe they might be the same thing. Maybe car parks could be a new hybrid urban typology. Perhaps the most mundane pf programmes could become the most significant. What if these non-places become places? What if these crossover points between private and public dramatized the change from individual to collective? What if the car - traditionally seen as anti-urban - became a friend of the city? What if the enthusiasm of custom car design spilled over from the fender to the tarmac? But you know, I wouldn't turn down those art gallery and concert hall type of projects in the meantime»

Sam Jacob, em entrevista à A10.

Sam Jacob é membro da FAT, que basicamente é um grupo de pessoas que se dedicam à arquitectura e arte sem recusar nenhum tipo de influência. Seja ela qual for. A FAT tembém produziu o internacionalmente famoso How to become a Famous Architect.

- A car park. The only open spaces in a city are parks and car parks. Maybe they might be the same thing. Maybe car parks could be a new hybrid urban typology. Perhaps the most mundane pf programmes could become the most significant. What if these non-places become places? What if these crossover points between private and public dramatized the change from individual to collective? What if the car - traditionally seen as anti-urban - became a friend of the city? What if the enthusiasm of custom car design spilled over from the fender to the tarmac? But you know, I wouldn't turn down those art gallery and concert hall type of projects in the meantime»

Sam Jacob, em entrevista à A10.

Sam Jacob é membro da FAT, que basicamente é um grupo de pessoas que se dedicam à arquitectura e arte sem recusar nenhum tipo de influência. Seja ela qual for. A FAT tembém produziu o internacionalmente famoso How to become a Famous Architect.

há blogues assim

Feitos de fragmentos sob fundo preto. E quando são feitos por amigos (como é o caso) a alegria da sua descoberta multiplica-se. Eis o FEU LA CULTURE.

Recomenda-se a visita também ao figaro figaro que, segundo me foi dito e se pode perceber, é mais um que carrega a arquitectura nas entrelinhas.

Recomenda-se a visita também ao figaro figaro que, segundo me foi dito e se pode perceber, é mais um que carrega a arquitectura nas entrelinhas.

O que levou aquelas 23 almas a juntarem-se?

Concordando-se ou não com o conteúdo, a carta contra o artigo de Maria Filomena Mónica sobre Boaventura Sousa Santos publicada hoje no Mil Folhas é absolutamente ridícula. Ridícula.

quinta-feira, 6 de janeiro de 2005

Sim, é para ti

Se eu disser que te amo em frente a esta gente toda, o que é que esta gente toda fica a saber?

De memória, roubado ao (saudoso) Dicionário do Diabo do Pedro Mexia

De memória, roubado ao (saudoso) Dicionário do Diabo do Pedro Mexia

Donativo global

Vendo os donativos que se vão acumulando penso nos activistas anti-globalização, ou nos defensores da alter-globalização (seja lá o que isso fôr). Não sei porquê, mas suspeito que serão capazes de encontrar um malefício qualquer nisto tudo, uma culpa qualquer dos estados ricos. Não compreendendo que toda esta ajuda só é possível devido àquilo que rejeitam.

quarta-feira, 5 de janeiro de 2005

E agora vamos a coisas realmente importantes

What 'Styles' Mean to the Architect

by Frank Lloyd Wright, 1928

«IN WHAT is now to arise from the plan as conceived and held in the mind of the architect, the matter of style may be considered as of elemental importance.

In the logic of the plan what we call "standardization" is seen to be a fundamental principle at work in architecture. All things in Nature exhibit this tendency to crystallize—to form and then conform, as we may easily see. There is a fluid, elastic period of becoming, as in the plan, when possibilities are infinite. New effects may, then, originate from the idea or principle that conceives. Once form is achieved, that possibility is dead so far as it is a creative flux.

Styles in architecture are part and parcel of this standardization. During the process of formation, exciting, fruitful. So soon as accomplished—a prison house for the creative soul and mind.

''Styles'' once accomplished soon become yard-sticks for the blind, crutches for the lame, the recourse of the impotent,

As humanity develops there will be less recourse to the ''styles'' and more style,—for the development of humanity is a matter of greater creative power for the individual—more of that quality in each that was once painfully achieved by the whole. A richer variety in unity is, therefore, a rational hope.

So this very useful tendency in the nature of the human mind, to standardize, is something to guard against as thought and feeling are about to take "form,"—something of which to beware,—something to be watched. For, over-night, it may "set" the form past redemption and the creative matter be found dead. Standardization is, then, a mere tool, though indispensable, to be used only to a certain extent in all other than purely commercial matters.

Used to the extent that it leaves the spirit free to destroy it at will,—on suspicion, maybe,—to the extent only that it does not become a style—or an inflexible rule—is it desirable to the architect.

It is desirable to him only to the extent that it is capable of new forms and remains the servant of those forms. Standardization should be allowed to work but never to master the process that yields the form.

In the logic of the plan we see the mechanics that is standardization, this dangerous tendency to crystallize into styles, at work and attempting to dispose of the whole matter. But if we are artists, no one can see it in the results of our use of it, which will be living and "personal," nevertheless.

There is a dictum abroad that ''Great Art" is impersonal.

The Universal speaks by way of the Personal in our lives. And the more interesting as such the deliverer is, the more precious to us will that message from the Universal be. For we can only understand the message in terms of ourselves. Impersonal matter is no matter at all—in Art. This is not to say that the manner is more than the matter of the message—only to say that the man is the matter of the message, after all is said and done. This is dangerous truth for weak-headed egotists in architecture who may be in love with their own reflections as in a mirror.

But why take the abuse of the thing for the thing itself and condemn it to exalt the mediocre and fix the commonplace?

All truth of any consequence whatsoever, is dangerous and in the hands of the impotent—damned. Are we, therefore, to cling to ''safe lies"? There is a soiled fringe hanging to every manful effort to realize anything in this world—even a square meal.

The Universal will take care of itself.

Let us tune up with it and it will sing through us, because of us, the song man desires most to hear. And that song is Man.

The question is now, how to achieve style, how to conserve that quality and profit to the fullest extent by standardization, the soul of the machine, in the work that is "Man." We have seen how standardization, as a method, serves as guide in the architect's plan, serves as a kind of warp on which to weave the woof of his building. So far, it is safe and may be used to any extent as a method while the ''idea" lives. But the process has been at work in everything to our hand that we are to use with which to build. We can overcome that, even profit by it, as we shall see. The difficulty is that it has been at work upon the man for whom we are to build. He is already more or less mechanized in this the Machine-Age. To a considerable extent he is the victim of the thing we have been discussing—the victim, I say, because his ideas are committed to standards which he now wilfully standardizes and institutionalizes until there is very little fresh life left in him. To do so is now his habit and, he is coming to think, his virtue.

Here is the real difficulty and a serious one.

What fresh life the architect may have is regarded with distrust by him, suspected and perhaps condemned on suspicion, merely, by this habituate who standardizes for a living—now, and must defend himself in it. The plan-factory grew to meet his wants. Colleges cling to the "classic'' to gratify him. His ''means" are all tied up in various results of the process. He is bound hand and foot, economically, to his institutions and blindfolded by his ''self-interest." He is the slave of the Expedient—and he calls it the Practical! He believes it.

What may be done with him?

Whatever was properly done would be to undo'' him, and that can't be done with his consent. He cannot be buried because it is a kind of living death he knows. But there are yet living among him those not so far gone. It is a matter of history that the few who are open to life have made it eventually what it is for the many. History repeats itself, as ever. The minority report is always right—John Bright pointed to history to prove it.

What we must work with is that minority—however small. It is enough hope, for it is all the hope there ever was in all the world since time began, and we believe in Progress.

These slaves to the Expedient are all beholden to certain ideas of certain individuals. They tend to accept, ready-made, from those individuals their views of matters like style and, although style is a simple matter, enough nonsense has been talked about it by architects and artists. So ''Fashion" rules with inexorable hand. The simple unlettered American man of business, as yet untrained by ''looted" culture, is most likely, in all this, to have fresh vision. And, albeit a little vulgar, there, in him, and in the minority of which we have just spoken, is the only hope for the architectural future of which we are going to speak.

The value of style as against standardized "styles'' is what I shall try to make clear and, to illustrate, have chosen from my own work certain examples to show that it is a quality not depending at all upon ''styles," but a quality inherent in every organic growth—as such. Not a self-conscious product at all. A natural one. I maintain that if this quality of style may be had in these things of mine, it may be had to any extent by Usonia, did her sons put into practice certain principles which are at work in these examples as they were once at work when the antique was "now.'' This may be done with no danger of forming a style—except among those whose characters and spiritual attainments are such that they would have to have recourse to one anyway.

The exhibition will become complete in the course of this series. The immediate burden of this paper is properly to evaluate this useful element of standardization with which the architect works for life, as in the "logic of the plan," and show how it may disastrously triumph over life as in the "styles" in this matter that confronts him now.

This antagonistic triumph is achieved as the consequence of man's tendency to fall in love with his tools, of which his intellect is one, and he soon mistakes the means for the end. This has happened most conspicuously in the architectural Renaissance. The ''re-birth'' of architecture. Unless a matter went wrong and died too soon there could be no occasion for "re-birth." But according to architects, architecture has been in this matter of getting itself continually re-born for several centuries until one might believe it never properly born, and now thoroughly dead from repeated "rebirth." As a matter of fact, architecture never needed to be born again—the architects who thought so did need to be; but never were.

A few examples may serve to show ''architecture" a corpse, like sticking a pin into some member of a cadaver. Such architectural members for instance as the cornice—pilasters and architraves—the façade and a whole brain-load of other instances of the moribund.

But architecture has consisted of these things. And architecture before that had the misfortune to be a non-utilitarian affair—it was a matter of decorating construction or sculpturing, from the outside, a mass of building material. At its worst it became a mere matter of constructing decoration. This concept of architecture was peculiarly Greek. And the Greek concept became the architectural religion of the modern world and became so, strangely enough, Just when Christianity became its spiritual conviction. The architectural concept was barbaric, unspiritual—superficial. That did not matter. Architecture was "re-born" in Florence on that basis and never got anywhere below the surface afterward, owing to many inherent inconsistencies with interior life as life within, lived on. I am talking of ''Academic'' architecture.

Of the three instances we have chosen, the cornice would be enough to show—for as it was, the other two were, and so were all besides. We are now attacking the standard that became standardized.